I’m Obsessed With Man-to-Man Marking

Having obsessive-compulsive disorder and ADHD co-morbidly is like being on the worst rollercoaster you’ve ever been on and never being able to get off. It just keeps going around and around and around, and every time it does, it feels like it’s getting worse and worse. It’s an interesting world the conditions create in your mind, and the only way to blur them out, or even put them to use in a positive way, is to find something that intrigues you, or, as we ADHD folk say, allows you to hyper-focus.

Over the last few weeks since watching Atalanta play Liverpool at Anfield and back in Italy, I’ve been hyper-focusing on one thing and one thing only. Man-to-man marking. More specifically, Gian Piero Gasperini’s man-to-man marking system. I’ve watched back footage, specifically the first half at Anfield, and tried my very best to learn exactly how the system is deployed and what happens to the opposition when it’s done correctly. The results are quite startling, to be honest.

It Takes Huge Cohones Marking This Way:

Gasperini’s deployment of the man-to-man system at Anfield was ballsy and full of gusto. To go that high in a press in one of the most hostile environments in European football would be regarded as tactical suicide among many in the game, but not Gasperini. La Dea deploys the system no matter the opposition, on any occasion, because there is true belief in the inner workings of the tactical plan. That was easy for everyone to see in not only the result but the way they stifled Liverpool time and time again in their build up.

The Italian manager’s split striker’s halted Liverpool’s progression through their two usual sources in their centre-backs. Virgil Van Dijk and Ibrahima Konate were unable to receive the ball and turn into space, and drive in the manner that they usually would against other systems. Atalanta’s marking of the rest of the Liverpool team further up the pitch stopped any sort of normal buildup happening when the Reds were in possession of the ball.

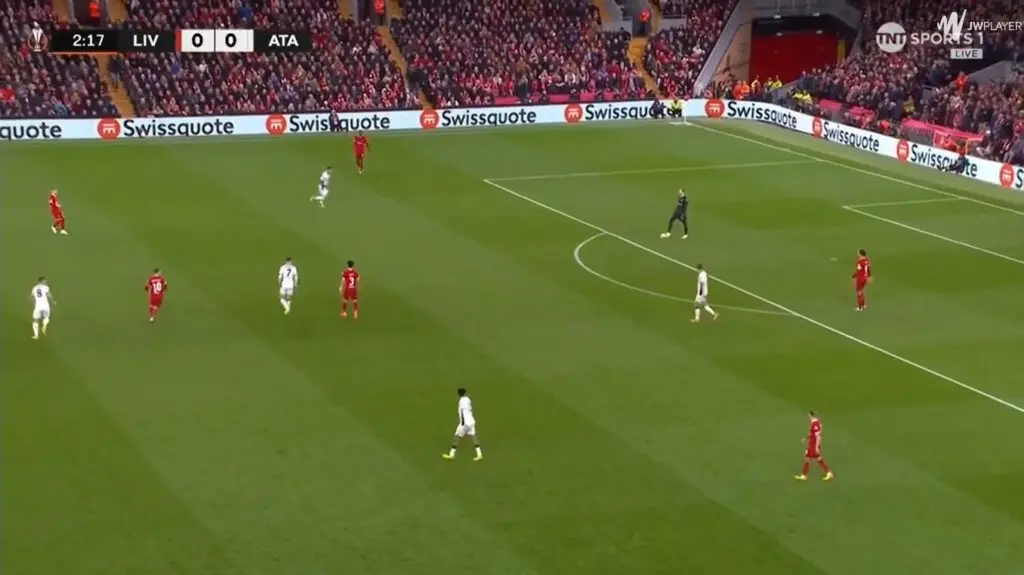

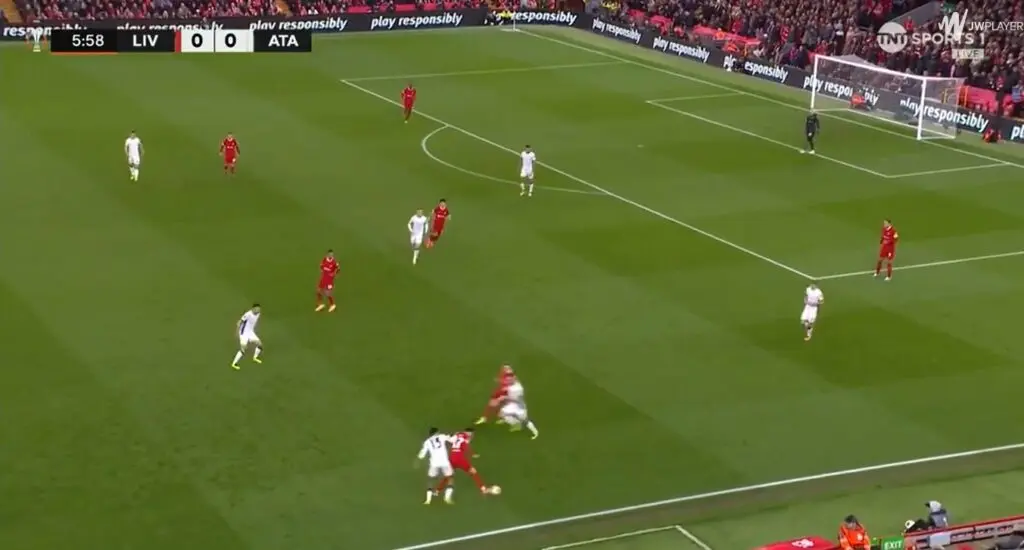

Caoimhin Kelleher is unlikely to have had that much of the ball in any of his games for the club prior, and the fact he did was a direct result of the man-to-man press being performed perfectly. Scamacca pushes over to Konate, De Ketelaere marks Van Dijk, and Ederson leaves his midfield position and moves up near the right wing spot to mark Kostas Tsimikas, as that was an out ball Liverpool tried to utilise in the early moments. Koopmeiners takes Endo, and Palasic marks Alexis Mac Allister closely.

There is no accurate route out for Liverpool in this situation other than to go long, which is what they do, and the ball gets recycled back to Atalanta. These are the scenarios a man-to-man system plans for. Stifle the opposition in their buildup, force them long, and trust your duel winners to win the battle from the long-ball. Once you win the ball back, try to play forward, utilise the wide areas and wing-backs in the manner Atalanta do, and look for cut-backs to the edge of the area.

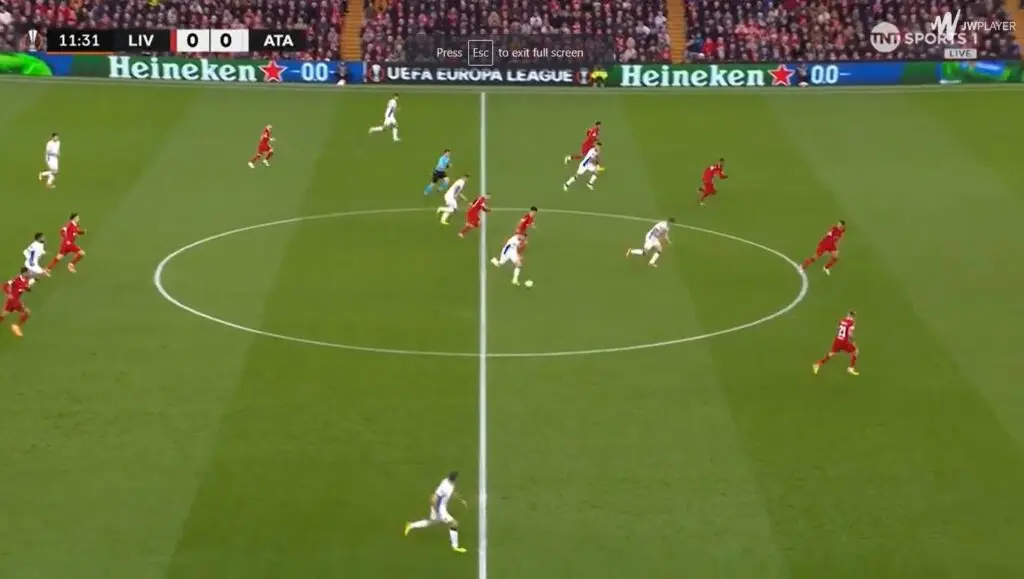

Another question to be asked is: How does the press look when the ball is not at the other end of the park? What if Liverpool begin to gain momentum further forward and pin the opposition back? Does the same principle remain? For the most part, yes.

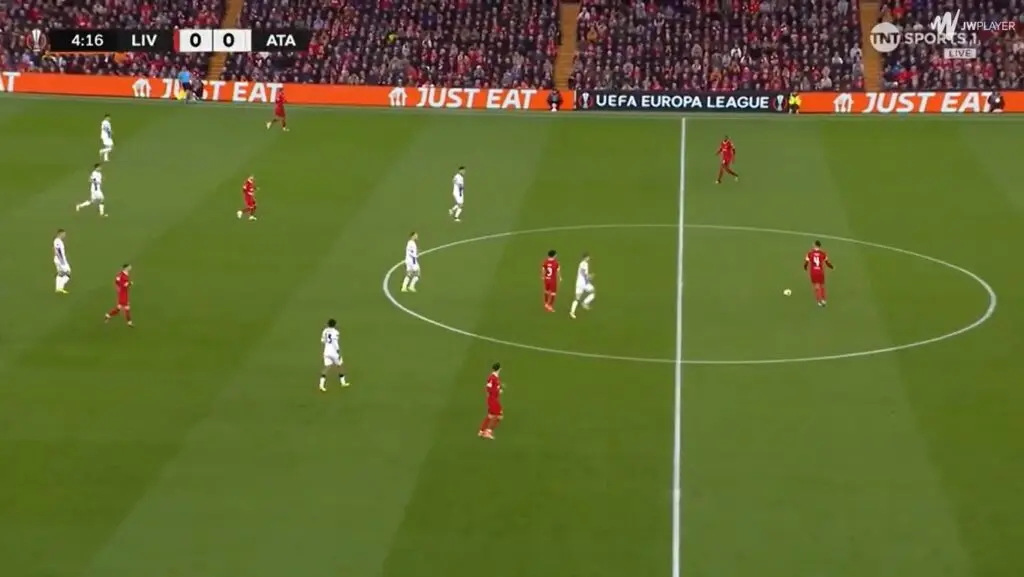

Atalanta remain man for man, using a 3-3-3-1 shape in this image, but in reality they are just blocking the passing lanes off to all the Liverpool players. In this particular image, Atalanta actually gets bypassed by a direct ball forward from Konate to Elliot on the right-hand side, which can happen and likely happened due to Scamacca’s press being a bit passive on this occasion, but this is just an example of how it looks when the opposition gains a bit of momentum and begins to play further up the park.

Liverpool tried to negate the effect of the man-to-man press by dropping Cody Gakpo deep, but he was followed wherever he went on the park. The man-to-man approach, Gasperini’s anyway, does not worry about rotations. If a centre-back has to come into central midfield, he’ll do it just to stop the ball from progressing. It’s a fluid system that is not obsessed with exact positions and players being in certain locations on the pitch; it’s sole mantra is to follow and pressurise, force back, and go long.

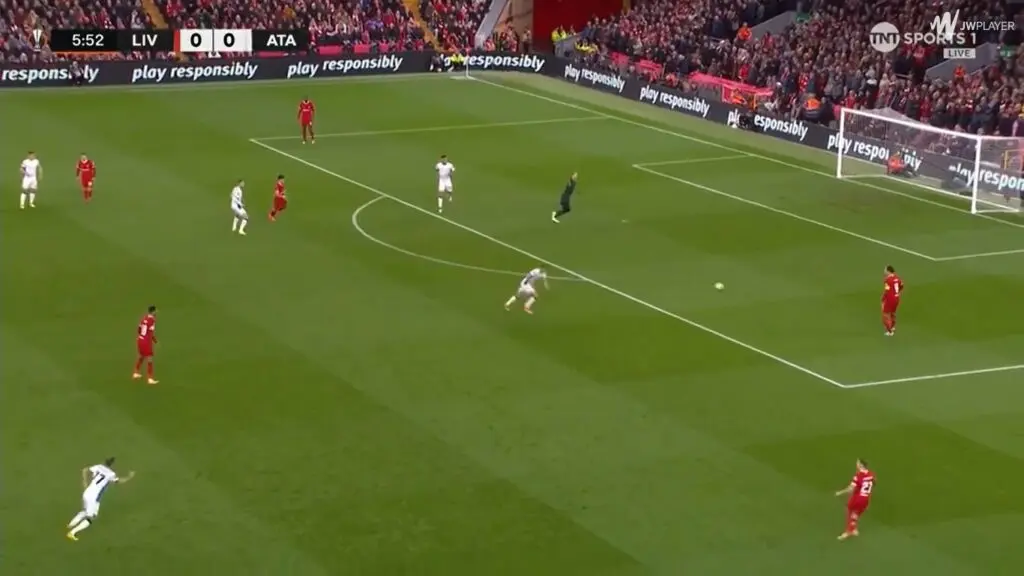

All these early clips are a mere five minutes into the game, showing how the approach can change the course of the match early on. Tsimikas is Liverpool’s only free man in this image, but the pass to Van Dijk has triggered a pressing response from Atalanta’s right-wing back, Zappacosta. The Italian rushes to Tsimikas, who forces the ball down the line to Curtis Jones, who, low and behold, is immediately man-marked by another Atalanta player. Again, forcing Liverpool to play certain passages and pushing them back towards their own goal. The man-marking system is in full affect.

The more aggressive and well-structured the man-to-man press is, the higher the likelihood you have of forcing the opposition back to the goalkeeper. There is also a much higher chance of the ball going long from the goalkeeper up the pitch, where your duel winners are more often than not expected to win the ball and allow you to go back the other way and possibly catch the opposition unstructured and in disarray.

Within this instance, Tsimikas receives the ball and literally has no other passing avenues other than the key in a man to man pressing system, the only spare man, the goalkeeper. The ball goes back to Kelleher, who goes long, and turns over possession.

A key cog in Gasperini’s system is a striker who can drop away from the opposition’s backline and into the spaces between the midfield and the defence. There are few players that can do that as well as Gianluca Scamacca. Again, these clips are all from the first half of Atalanta’s game against Liverpool at Anfield, and even within 9 minutes, you can see the clear tactical plan of the team.

The Italian manager likes Scamacca to drop deep because it allows his midfielders to make runs beyond him, third man runs if you will. It drags defenders in and opens up space in behind, and Atalanta actually scored their third goal of the night by doing this exact thing tactically.

The man-to-man turnover:

Another key part of the man-to-man setup is turnovers. If you can get a turnover in the middle of the park while utilising the tactic, as we’ve mentioned previously, you catch the opposition unorganised. Atalanta did this early on against Liverpool in the game, and put them on notice to be careful around the middle of the pitch in possession. The fact La Dea have their wing-backs so high is incredibly dangerous if you can create a transitional moment, and they proved that 12 minutes in when they came close to scoring, with Zappacosta on the wide overlap and five Atalanta players flooding into the box to try create a scoring opportunity.

A brilliant example of how the press works came in the 22nd minute, when space opened up centrally. The opportunity arose for Curtis Jones to come into the space and get the ball, which is something that in usual games he’d likely have had the time to do, while also turning and facing the play, and springing an attack for Liverpool. The England under-21 international, however, wasn’t afforded that much space and time on this occasion, with the Atalanta centre-half following him all the way back into his own half and forcing the ball directly back to Caoimhin Kelleher.

Principles of the system:

The main principles of the system are to force the opposition into situations they are not comfortable with. The system aims to block the ball into the better individuals on the pitch, and stop the team building and sustaining attacks due to the amount of passing lanes blocked off. It’s a high pressure aggressive pressing shape that tries to make the opposition play the game long, to play into the hands of probability on the long-ball, and hopefully enable your team to pick up the second ball and spring an attack going the other way.

To hurt the opposition while deploying this system, the wide areas are valuable. Wall passes from your centre-forward back into your central midfielder are vital, and third man runs beyond the centre-forward are also something to try and use as much as you can. Wing-backs are an asset, as the cut back cross when you win the ball on a transition is something a lot of teams struggle to defend against.

You may need a strong centre-forward to play this system unless you can seamlessly play out of the press yourself. Atalanta struggled at times against Liverpool in possession when they were pressed, but were helped majorly by the presence and ability of Scamacca up front.

The best assets against the man to man press is to pull the opposition ragged with your own teams rotations and keep on moving the ball as quick as you can between one another. Another vital asset is high pace dribbling at the opposition, which takes the idea of man marking effectively out of the game. That leans more towards being bailed out by individual brilliance however as opposed to actually tactically breaking down the system, but sometimes there is absolutely nothing wrong with that.

As I said, and as you’ve probably gathered, i’m obsessed with man to man marking. I hope this article has made you just as obsessed as me!